In October 1914 at the age of 18 years and 6 months, John Charlesworth from the East Midlands of England, enlisted in the British Army and was posted to the 2/8th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters (Notts & Derby Regiment). Like so many soldiers of that generation, John did not survive the Great War, and is buried in the small graveyard of St Flannan’s Cathedral in Killaloe. How did this young Private, who signed up to fight in the trenches of the Western Front, find his final resting place on the banks of the River Shannon?

In October 1914 at the age of 18 years and 6 months, John Charlesworth from the East Midlands of England, enlisted in the British Army and was posted to the 2/8th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters (Notts & Derby Regiment). Like so many soldiers of that generation, John did not survive the Great War, and is buried in the small graveyard of St Flannan’s Cathedral in Killaloe. How did this young Private, who signed up to fight in the trenches of the Western Front, find his final resting place on the banks of the River Shannon?

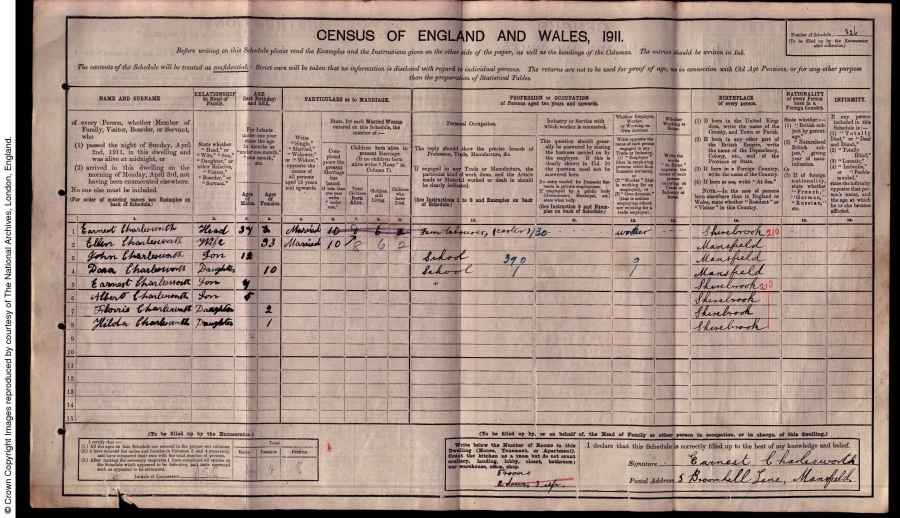

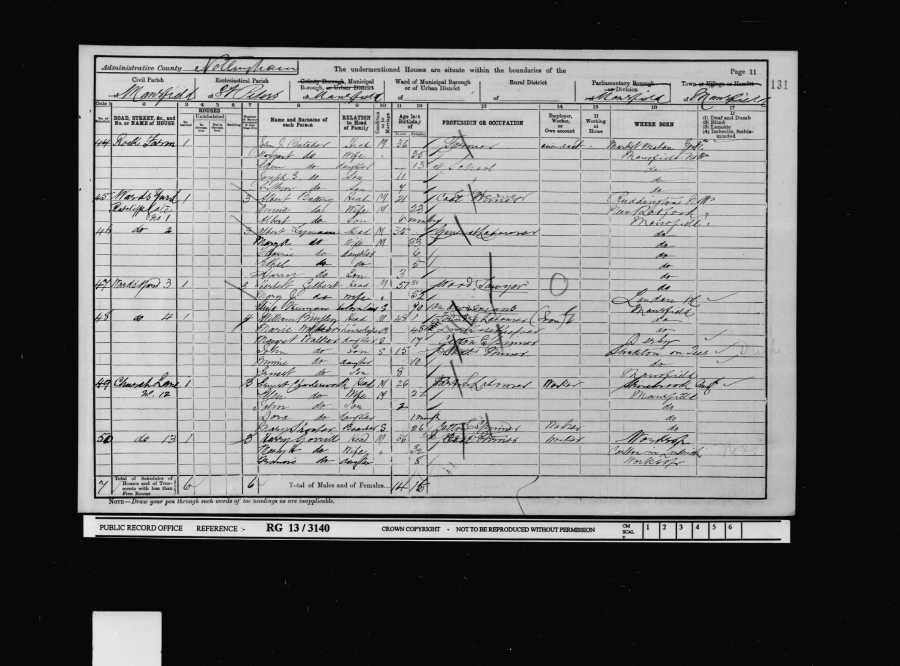

John was the eldest son of Earnest and Ellen Alice Charlesworth from Mansfield in Nottinghamshire, and had five siblings – Dora, Earnest Jr, Albert, Floris and Hilda. After attending school he spent some time working as a miner in the Lang with Colliery a few miles north of Mansfield.

Shortly after war broke out John signed up and was attested into the army on 28 October 1914. His unit was originally held in readiness to combat a German landing on the East Coast and also as a reserve to the 1st lines on the Western Front. The soldiers spent the next 18 months moving between various locations in England and training for the day they would cross the English Channel to fight in France.

It was events across the Irish Sea, however, which threw these men into their first battle. On Monday 24 April 1916, the 2/8th Battalion, as part of the 178th Brigade “received orders to hold itself in readiness to move at once to an unknown destination”. The destination was Dublin. That Monday morning Irish rebels had taken over the GPO and other buildings in the city with the aim of achieving independence from Britain. The Easter Rising had begun.

The Sherwood Foresters landed in Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) at 7am on Wednesday 26 April and the 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions proceeded towards the city along the coast road and through Ballsbridge. As the troops reached the junction of Northumberland and Haddington Road they came under fire from rebels in a house at number 25. This exchange marked the beginning of the battle of Mount Street Bridge in which the Sherwood Foresters suffered significant casualties. By late in the day, they had lost around 220 men in dead and wounded. Many were young recruits, some of whom had not yet learned to fire a rifle. John was fortunate enough to survive the carnage at Mount Street and as the week wore on, British reinforcements and firepower overwhelmed the rebels who surrendered on Saturday 29 April.

As the country remained under military law the Foresters were sent westwards, first to Athlone, then on to Loughrea and Athenry where, on Easter Monday, under the command of Liam Mellowes, about 500 poorly armed rebels had gathered but later retreated and dispersed. Between the end of April and the first weeks of May, the 2/8th patrolled the area around east Galway, principally as a show of force but also to capture arms and rohttp://www.mcmahonenglish.ie/about-us-limerick-solicitors.aspxund up any suspected rebels. On May 16 they were sent to Killaloe to conduct a similar operation and it was here that John Charlesworth met his unfortunate fate.

The Foresters arrived in Killaloe on Tuesday morning 16 May and were billeted in the Lakeside Hotel on the Ballina side of the river. The battalion’s commanding officer Colonel Oates later wrote:

“Several boats were moored to the bank in the meadow below the Hotel, and the men had been warned not to meddle with them. Three men however disobeyed the order and entered one of the boats…”

By all reports the river was high and the current was strong at the time and the men had no oars. The boat soon got out of control and was carried downstream where it was smashed against the sluice gates. One of the soldiers held on to the gates and was rescued shortly afterwards. The other two were swept under the gates and reappeared about 25-30 yards downstream. At this point one soldier disappeared completely from view and was not seen afterwards. The other was rushed along for about 500 yards when another soldier from the bank jumped in the river in a failed attempt to rescue him. Both men then continued down the river and under the bridge where they were eventually rescued by local boatmen. These boatmen were later named at the inquest and commended for their actions. They were Michael Barry, Peter Nunan, Thomas Maloney, William Malone, Michael Keeshan and William Lucas. They were directed as to the men’s location in the river by Constable Jeremiah Mahoney from his vantage point on the bridge. The two soldiers were unconscious when they were pulled from the water but were revived by Dr McCormack and Constable Mahoney. The body of the other soldier, John Charlesworth, remained missing.

Seven days later on Monday 22nd May, John’s body was discovered by two fishermen in the water near Moys (behind Clarisford Park). William Ives stated that Thomas Warren:

“drew his attention to a dark object in the water; he knew that a soldier had been drowned in the river on the 16th and when he went to the object he found that it was the body of a soldier; he secured the body in the water near the bank, and informed Constable Kissane.”

Constable Kissane searched the body and found a disc around the neck, it bore the name J. Charlesworth and the letters c of e 8 N and D; in the pockets he found an army pay book, two rosary beads, a belt, some postcards, letters, photographs and 3 shillings 1 1/2 pence. The body was examined by Dr P.J. Holmes who established that the cause of death was drowning.

In the meantime, John’s Battalion had left Killaloe and it took some time to contact the commanding officer Colonel Oates to inform him of the discovery of the body. Oates had earlier wired the District Inspector Alfred McClelland stating that: ‘any expenses incurred in connection with the deceased’s funeral would be defrayed by the military’.

McClelland wired the Chief of Police at Mansfield to inquire as to the family’s wishes for the burial – whether it should be carried out by a priest or a Protestant clergyman. He also wired the commanding officer at Limerick and asked if a firing party could be sent down to Killaloe to give the deceased a military funeral, for “although he had died at home he had, nevertheless, died for his country”.

And so, John Charlesworth was laid to rest in the small graveyard in Killaloe. He is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and by Nottinghamshire County Council on their Roll of Honour which gives John’s age at death as 20.

A closer examination of his age however, reveals that John was actually much younger. The 1901 and 1911 censuses show that John was in fact born in 1899. He appears in the 1901 Census living in Mansfield with his father Earnest, mother Alice and sister Dora. He is listed as being two years old. In 1911 he appears as 12 years old. This means that in October of 1914, John lied to the Army about his age, and signed up to fight in the Great War at the tender age of 15. The tragedy of his death is compounded by the knowledge that this was not a battle-hardened old soldier but a teenager full of adventure and mischief who got into a boat with his mates and drowned in a river far from home a mere 17-year-old boy.

Copyright: Darren O’Conaill

I have now traced John to my family his grandfather was a David charlesworth born 1832,the charlesworth family have resided in langwith ,bolsover ,shirebrook for hundreds of years one of johns family was a officer killed in Monte Casino in ww2 ,a lot of Charlesworth’s worked in langwith pit,

LikeLike